The Random Access Channel (RACH) in LTE has a key role of providing up-link transmission synchronization to the UE. Once the UE has achieve up-link synchronization, the eNB can schedule orthogonal up-link transmission resources to it. When does the UE need to perform Random Access? Well, the UE require to perform random access in the following scenarios:

- UE initial attach

- RRC reestablishment after Radio Link Failure (RLF)

- Handover to a new cell

- If the UE sends up-link data or receives down-link data while RLF occurs

- When the UE trigger location services (for example a 911 call)

Physical Random Access Channel (PRACH) Planning

In LTE there are 64 PRACH signatures available per cell (remember fighting collisions with the few 16 in UMTS?). The 64 signatures are generated from cyclic shifts of root Zadoff–Chu sequences. Zadoff-Chu sequences have many properties, but linked to PRACH planning there is one that is above all: If the cycle shift (Ncs) used is larger than the maximum round-trip propagation time in the cell plus the maximum delay spread of the channel, then the the cross-correlation between different preambles based on cyclic shifts of the same Zadoff–Chu root sequence is zero at the receiver. Which means that there is no intra-cell interference from multiple random-access attempts using preambles derived from the same Zadoff–Chu root sequence!

So, if preambles from different Zadoff-Chu sequences are not orthogonal and preambles from cyclic shifting the same Zadoff-Chu single root are orthogonal , then cyclic shifting a single Zadoff-Chu root should be favored. But, this is not possible all the times. To explain this, let me address the following table:

The length of the Zadoff-Chu root sequence is 839 samples. Each value of PrachCs defines the number of cyclic shifts the root sequence has. For a PrachCs value of 1 there are 13 Cyclic Shift Samples so from 1 root sequence of 839 you can get 839/13=64 Cycle Shifts per Zadoff-Chu sequence. This means that from a single Zadoff-Chu root sequence you can get all the 64 signatures. But imagine what happened at PrachCs 12 when we have 119 Cyclic Shift Samples so, from 1 root sequence of 839 you can get 839/119=7 Cycle Shifts per Zadoff-Chu sequence. In order to get the 64 signatures, more Zadoff-Chu root sequences are required (in total, 10). As you can see the total number of sequences is 64, but resulting from different combinations of the number of root sequences and cyclic shifts.

There are 838 root Zadoff-Chu sequences available for preambles. The parameter rootSequenceIndex tells the UE which sequence it has to use.

The UE is given a pointer (the logical root sequence number) which establish the location of the Physical root sequence index mapped in the table above. For example a logical root sequence number of 27 indicates a physical root sequence index of 727. You get it by looking at the range of the logical root sequence (in this case 24-29) and where is located the logical sequence number from the range (in this case is 3 positions over 24).

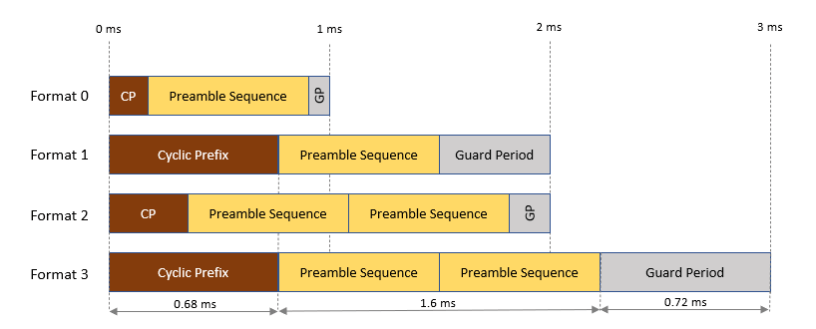

The value of PrachCs depends on the cell size (or cell radius/range). If the cell has a coverage of 2 Km then the PrachCs should be 4. But the cell distance also shapes the random access format. There are 4 random access preamble formats defined for FDD:

What is the main difference among these preamble formats? Each format is intended for a maximum cell range and the range is limited by the guard period. The guard period is the time difference allowed between an UE transmitting close to the NB with an UE transmitting at cell edge. Format 0 allows a cell to have up to 14.53 Km of cell radius, Format 1 up to 77.34 Km, Format 2 up to 29.53 Km and Format 3 up to 101.88 Km. We can select between preamble format through parameter PRACH Configuration Index:

The RACH density indicates how many RACH resources are per 10 ms frame. RACH density is defined in the table above through the sub frame number column. It is recommended that all cells belong to the same site have the same PRACH configuration. For example in a 3 sector cell, using preamble format 0 with RACH density of 1, PRACH Configuration index might be 3 for cell A, 4 for cell B and 5 for cell C.

Other RACH Parameters

There are more parameters that controls RACH. I thought that might be a good idea to check one of the available service providers and discuss their network settings. Note that this is SIB 2 (list 2) information which is given to the UE in the BCCH_DL_SCH:

Let me start with the parameters in #2. Here there is the RACH_ROOT_SEQUENCE, which we have discussed before is a pointer to the location of the Physical root sequence index. In case of OPERATOR B we can extract this value from the table, which is 336.

Then under PRACH Configuration information we have:

- PRACH configuration index. Here is an important difference between both operators: OP-A has it set to 19 and OP-B to 5. This means that both operators maintain a RACH density of 1, while OP-A uses Preamble format 1 and OP-B preamble format 0. This could indicate that the OP-A NB has a bigger coverage.

- High Speed Flag. High speed flag for PRACH preamble generation determines whether an unrestricted or a restricted set has to be used by the UE. False = Unrestricted; True = Restricted

- Ncs configuration. This parameter was discussed before and shows how many cyclic shift per Zadoff-Chu root sequence we have. Both OP set this to 12.

- PRACH frequency offset. Defines the location in frequency for the PRACH transmissions. For UL scheduling its recommended that PRACH is located next to PUCCH either on the lower or upper edge of the bandwidth because UL PRB allocation for UE consist of consecutive PRBs. Its value depends on how many PUCCH resources are available and bandwidth.

There are a couple of parameters I want to highlight in the RACH configuration common section:

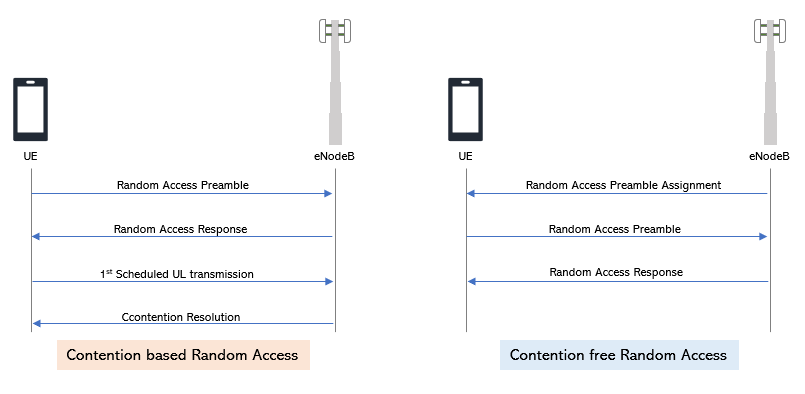

- Number of access preambles & size of RA preambles in Group A. These two parameters are used to reserve (or not) RACH preambles for contention free random access. If there is no size of RA preambles in Group A, means that all the preambles defined in the number of access preambles parameters are Group A (contention based). Else the group B is calculated as the number of access preambles minus size of RA preambles in Group A.

- Power ramping parameters. Here the power ramping step establishes the increment of power in terms of dB that next RA has to been done in case the previous was unsuccessful. The initial preamble power is the value of transmitted power the UE has to set the initial RA preamble. In these two operators the strategy is very different: one starts in low initial preamble power and high ramping steps, while the other takes less aggressive steps, but with a much higher initial preamble power. Which one you think is better?

Contention based and contention free Random Access

If the UE chooses randomly a preamble sequence and randomly transmitted it, chances are that a conflict might occur. Contention based random access protocol provides a way that in case that 2 or more UE arrives with the same RA preamble at the same time at the eNodeB, only one keeps the access procedure while the others start the whole process again. On contention free (or non contention based) random access is the eNodeB the one that assigns a random access preamble to the UE (reserved preambles in Group B, if any) so conflict is avoided. This is useful when time is critical, for example at handover.

As you can see, the topic of random access is loaded with theory, but in practice there are only few parameters to play with. Still network differ a lot on how they treat random access (you have experienced with the two examples I have provided). I hope it has help you in understand better these concepts. As for me, there is enough RA for today. Thanks for reading!!!

Cheers!

Diego Goncalves Kovadloff

References:

Erik Dahlman, … Johan Sköld, in 4G LTE-Advanced Pro and The Road to 5G (Third Edition), 2016

LTE – The UMTS Long Term Evolution: From Theory to Practice Stefania Sesia, Issam Toufik and Matthew Baker. 2009 John Wiley & Sons.